"The New York Game"

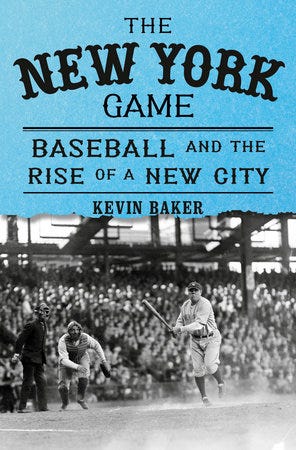

Interview with Kevin Baker, author of "The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City"

The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City is a new book from Kevin Baker that explores the early impact of New York and New Yorkers on the game we know today. It's a fascinating look at the hustle of post-Civil War America and the Gilded Age, full of familiar names and men lost to history, plus the establishment of leagues, the rise of broadcasting, the minor leagues, and the eventual integration of Black and Latino players. Kevin is a contributing editor for Harper's, and has published in The New York Times, The New Republic and New York Observer. He is also the co-author of Reggie Jackson's Becoming Mr. October. Part 2 of our discussion will appear next week.

So why is it “the New York Game”?

Baseball as we know it was invented in New York City. The sport has always gone to great lengths to deny these origins, even concocting the lie that Abner Doubleday invented it in one afternoon in 1839, along the banks of the Glimmerglass, in Cooperstown, New York.

This is disputed?

Not really. It’s a well-established lie. You know who’s not in the Hall of Fame? Abner Doubleday.

Doubleday had nothing to do with it?

No. Abner Doubleday was the Forrest Gump of the 19th century. He always seemed to be anywhere anything was happening. The first shot of the Civil War, “penetrated the masonry [of Fort Sumter] and burst very near my head,” he later recalled, and in turn he “aimed the first gun on our side in reply to the attack.” He rose to the rank of major general, sustained two serious wounds, helped to hold the Union line on the first day of Gettysburg, and took the train with President Lincoln back to the battlefield a few months later, when the president gave his Gettysburg Address. He read Sanskrit, corresponded with Ralph Waldo Emerson, commanded an all-Black regiment of troops, attended séances at the White House with Mary Todd Lincoln, obtained the first charter for San Francisco’s cable cars, and served as president of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society. But he did not invent baseball.

No one really thought he did, even when the myth was contrived. The whole idea was to find a quaint, charming American village like Cooperstown to represent all the quaint, charming little towns where it might have started. And thus keep its origin story out of the big, dirty, multiethnic, corrupting city.

But why Doubleday?

Albert Spalding, the pitcher-turned-sporting-goods-magnate who hired the “Origins Committee” in 1905, was a Theosophist, along with Doubleday. It’s as if a bunch of Scientologists had decided to replace James Naismith as the inventor of basketball with L. Ron Hubbard.

So baseball was really urban game?

Yep. And the urb where the modern game was perfected, was New York City. As David Block in Baseball Before We Knew It and the great John Thorn in Baseball in the Garden of Eden make clear, mankind has been playing some form of bat-and-ball game since we swung down from the trees to the savanna (which we probably noticed would make a pretty good ballfield, if someone would just cut the grass…Hmm: could baseball be responsible for human evolution? Does it want to be?).

There were all sorts of variations on the game played in America, most of them brought over from England. There was “wicket” in Connecticut (which George Washington reportedly played in Valley Forge); “the Philadelphia game"; and “the Massachusetts game,” in which there was no distinction between fair and foul ground, you could hit the ball in any direction, and players were put out only by being hit on the basepaths with a thrown ball (which was rubber). John Thorn, I know, favors this as being a more exciting and athletic game. He may be right—but how do you put a stadium around such a thing?

And the New York game wiped them all out?

Yep.

Why?

For many reasons. Mostly because, like New York’s merchant princes, the city’s baseball players kept experimenting, kept inventing new rules and tactics: the hardball, the bunt, the stolen base, the curveball. One local club, the New York Knickerbockers (not to be confused with the dreadful basketball team of the same name), kept writing all the changes down. And when the Civil War came, the New York game went all over the country. It won this very Darwinian struggle.

Because…?

It was quick, for one thing. We never think of baseball as fast, even after all the recent rule changes. But it was. As late as 1918, a major-league game between the New York Giants and the Philadelphia Phillies lasted only 58 minutes—which, granted, is generally about all you wanted to see of the Phillies. Mark Twain claimed it was “the very symbol, the outward and visible expression of the drive and push and rush and struggle of the raging, tearing, booming nineteenth century.” I mean, granted, this was a time when people went to listen to three-hour speeches for entertainment. But still.

Who played the game?

Everyone. Baseball was a tremendously democratizing sport at the beginning, played by men from all classes and background. Early on, in and around New York, there were clubs made up of clerks and shipbuilders; of firefighters and policemen; of actors, newspaper reporters, schoolteachers, hatters. There were even clubs composed entirely of milkmen and eye doctors.

The only people who weren’t much included, nearly from the beginning, were men of color. There were at least 55 African-Americans who played major- or minor-league ball through 1884, but they were not wanted, and were driven from the game or banned outright. It’s a horrible story, like that of racism in general, the greatest blotch on American life. Yet there is inspiration to be found in those who fought back. Like people of color in every other part of the struggle for civil rights, Black men made a way where there was no way, starting their own teams and leagues, and eventually forcing their way back into the white game.

Let’s get down to the matter at hand. When did the Dodgers hit the scene?

The Dodgers started life in Brooklyn, originally as the “Grays,” in 1883. They were in a major league (the long-defunct American Association) by 1884, and in that capacity they actually played the National League’s New York Giants in the very first “Subway Series” in 1889—15 years before there was a subway! The team would continue under many different names: the Bridegrooms, the Superbas, the Robins, the Bums, as well as the Dodgers, for “Trolley Dodgers,” which was a derisive nickname that Manhattanites used to hurl at their Brooklyn neighbors. This was very strange, as there were trolleys running all through Manhattan at the time. It’s as if we were to sneer today that Brooklyn residents are “straphangers.”

Who ran the Dodgers?

For many years, mostly corrupt machine politicians and gamblers—same as the types who started and/or usually owned the New York Baseball Giants and the New York Yankees. To have a club in New York—to run any entertainment—you had to pay off to the machine, Tammany Hall, and baseball was a constant object of fascination to gamblers as, sadly, it seems to be again today. The big exception was Charles Hercules Ebbets, who started out printing scorecards and selling tickets for the team, and ended up saving them from moving to Baltimore, taking over the franchise, and building Ebbets Field, probably the most beloved ballpark there ever was in New York.

Were they any good?

At times. They ran away with the National League pennant in 1899 and 1900, won again in 1916 and 1920. But they were generally considered eccentric, lovable losers, who could never quite win a World Series. All that began to change in the late 1930s, when a series of remarkable men—remarkable in very different ways—took over the club: Larry MacPhail, George V. McLaughlin, Branch Rickey, and then Walter O’Malley. They made the Dodgers trailblazers, when it came to radio and television broadcasting, night baseball, building a farm system, and, above all, finally breaking down the color wall. To their everlasting credit, they were the team, under Rickey, that signed Jackie Robinson.

The Dodgers were, all in all, as close as New York has ever come to fielding “America’s team.” Then—they went to Hollywood.

And the Yankees were their great rivals?

Yes. The two teams have now played in the World Series on 12 different occasions—far and away the record. From 1941-1956, they met in the Series seven different times. Since they absconded to L.A., the Yanks and Dodgers have now met five more times, and they have given us some of the most memorable World Series moments in the history of the game.

Let’s leave those for next week. Who do you like this year?

I picked the Yanks to win in six. Which is based upon my careful, honest appraisal—but which I realize means next to nothing. This Yankees team could just as easily get swept. As a great man once said, “There’s no predicting baseball.”

Kevin's book is now available from Penguin Random House. Order it at your local bookstore or from Amazon!

Next Week: The Long Saga of the Yankees vs. the Dodgers.