Excerpt 2 from "Double Play on the Red Line"

A fictional Jack Brickhouse considers what the game would be like if Black ballplayers hadn't been excluded from the majors and the best player he ever saw.

Double Play on the Red Line is the new novel from Dr. Rajesh C. Oza, a beloved and frequent contributor to Bardball. The novel explores race, class, caste and justice with the story of a Cubs rookie phenom in the 1950s — Ernie, but not THAT Ernie — who unjustly spent decades in prison before his debut. The book is an examination of the American Dream, a tale of justice in action, and a love letter to summers on the north side of Chicago.

For the first excerpt of the book, posted last week, click here.

To buy the book from Third World Press, click here.

“I love the question you have batting fourth. Wheee!” Jack chirped. “I’ve always been partial to cleanup hitters, so I’ll do my best here. Hmm. How great could Ernie have been? That’s a tremendous filler for a long rain delay. I might just use it one of these sloppy, wet days when the umpires don’t want to call it a day, and the tarp goes on and off, on and off the field. Might be today.” He paused, clasped his hands together as if they possessed a precious keepsake, remembered that he had retired and passed the broadcaster’s microphone to Harry Caray. “Well, I’d use it if Harry invites me back as a guest announcer on television. Or more likely Vince Lloyd and Lou Boudreau on the radio side. On rainy days, I used to dig deep into the memory file to fill dead broadcast time. As for Ernie, he played shortstop. So let’s measure him against the best who ever played on the left side of the infield. Always think about the historical record when sizing up contemporary ballplayers.”

Jack ran his manicured fingers through his thinning and graying blond hair. He polished his glasses on a silk handkerchief, rubbing the history he had seen into a story. He looked out the diner window at the gathering clouds. “Could rain today. Hope we don’t get an Indian Monsoon.” I appreciated the reference of incessant rain from the Subcontinent and encouraged Jack with a nod. He continued, “In terms of today’s shortstops, I hear this youngster Cal Ripken’s looking pretty good. But let’s give him some time before putting him in the Hall of Fame. He comes from a solid family with his Old Man teaching him the right way to play, The Oriole’s Way.

“On the other end of the Cooperstown spectrum, there was Honus Wagner for the Pirates. Did you know that he was one of the first five original inductees into the Hall of Fame? I was just a twenty-year-old kid when he made it. Never saw him play, but baseball old-timers told me he was the best.” Jack saw me smiling at his reference to baseball old-timers and reciprocated with a chuckle. He looked like a satisfied Buddha with glasses. It was hard for me to imagine someone older or wiser than Mr. Brickhouse. “Old Hans could do it all: hit for average, hit for power, field, and steal bases. Boy, could The Flying Dutchman round those bases. What I wouldn’t give to watch a scratchy old film of Wagner running bow-legged from first to second.”

A few folks sitting near us were eavesdropping on our conversation. They were of Jack’s generation. One of them asked, “Hey Jack, how good was Lou Boudreau at short?”

“Well, hello, old buddy. Good question about my old broadcasting partner. Yes, Handsome Lou was slick in the field. More importantly, he deserves the distinction of having had the greatest baseball season ever.”

The old buddy asked a follow-up question. “Greatest ever?”

Jack gleefully rubbed his hands together as a kind of prayer fire. He then held them six inches apart. “Playing shortstop, he led the entire majors in fielding in 1948.” He moved the hands out a couple more inches. “Batted .355.” The outstretched arms were now even with his body, fingers poised like pistols at our neighboring table. “Best defensive and offensive player that year. Voted MVP.”

Our fellow diner said, “That’s good enough for me.” He tipped his cap toward us and returned to his meal.

Jack turned back to me and made fists out of his handguns. He pounded the table twice. “Very good. But what made his 1948 season the greatest ever was that Lou managed the Cleveland Indians to the World Series championship.”

I replied, “Wow. He must have been the youngest player-manager to pull that off.”

“Bucky Harris has that honor. But The Good Kid was just four years older. Only 31.” With his fists open and arms stretched out longer than a Louisville Slugger, Jack continued, “But there’s more. Along with the Indians’ owner, Bill Veeck, Lou integrated the first Negro Leagues player into the American League. Larry Doby, who was overshadowed by Jackie’s arrival in 1947, but, boy, was he something special. Actually, more than Bill or Lou, Larry deserves the credit for pioneering integration of the American League. Eventually, he became the second Black man to manage in the majors. As for Lou, he also made the call to have the ageless Satchel become the first African-American to pitch in the World Series.”

Wanting to sound like I belonged with the diner’s baseball Buddhas, I intoned, “A season to remember. A man for all seasons.”

Jack said, “I remember Lou saying, ‘That was my year. It was like I had angels on my shoulders.’ Funny thing is it might’ve never happened. With his good looks, he could’ve been an actor instead.”

I considered my prospect of doing anything meaningful before I turned 31. Slim to none.

I wondered if middle-aged Ernie could still put on a uniform and play. I pictured the peanut vendor as among the best to have played the most difficult position in baseball. Simply trade the gray hawker’s uniform for the bright-white and pinstriped-blue jersey. Just like he covered a lot of ground in the bleachers snapping quarters in exchange for peanut bags, Ernie could have done the Cubs proud covering himself with glory as a shortstop with quick hands and long range. “Excuse me, Mr. Brickhouse. No disrespect for the stars from yesteryear. But where would Ernie have fit into your pantheon if he had played in the majors? You think he can still play?”

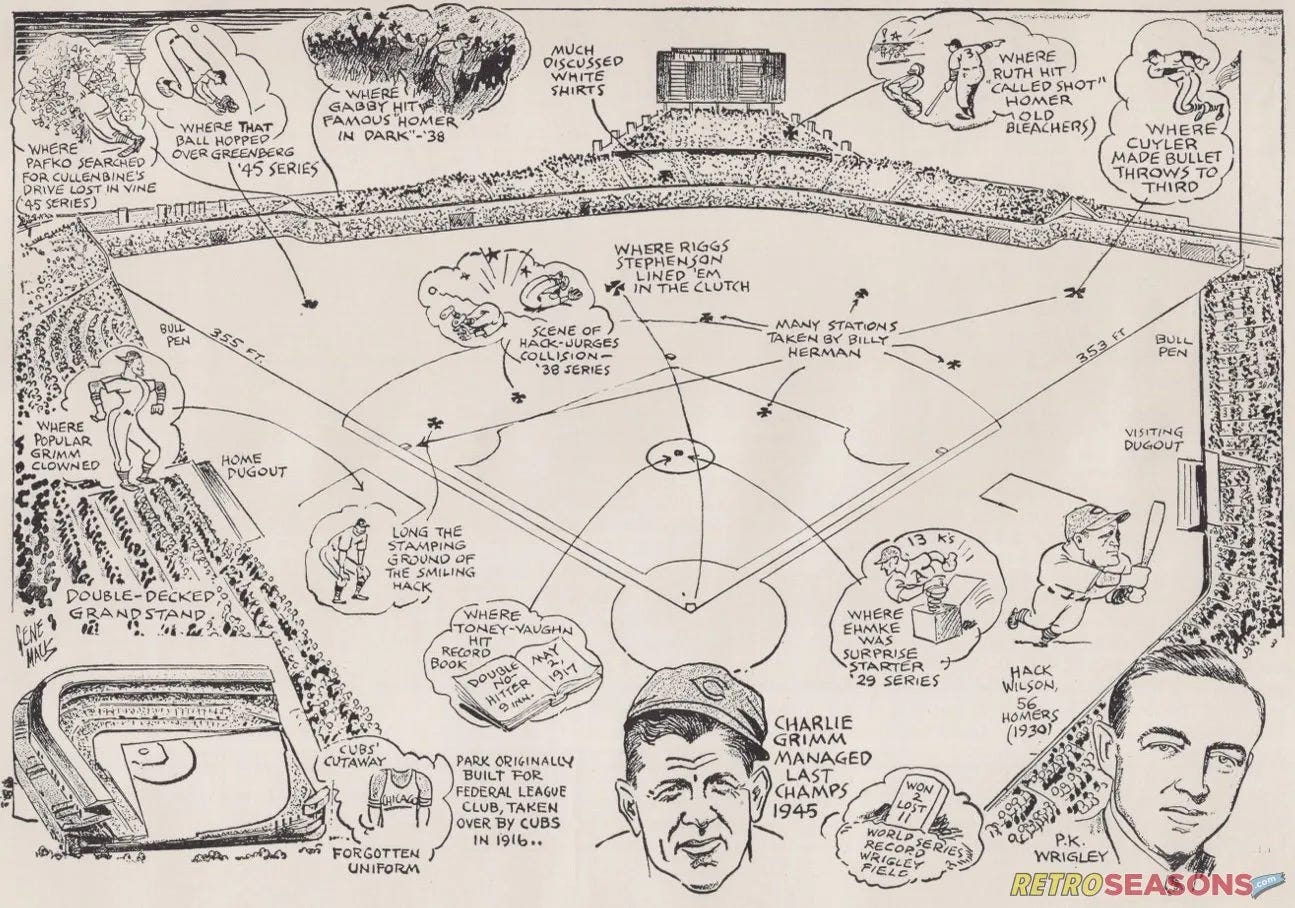

“No, he’s no Satchel Paige playing in his fifties. No way Ernie can get out there today with that bad eye of his. But I’m sure Ernie could have bested Honus Wagner. He could have hit more home runs than all of the great shortstops. I saw him play one time at Comiskey Park in the East-West Game featuring the best of the best from the Negro Leagues. From that one game, I knew Ernie had what all superstars have: talent plus charisma. That was the game where I saw Louis Armstrong throw out the first ball. Old Satchmo also played the National Anthem on his horn. All kinds of baseball fans flocked to that game. Made no difference whether you were Black or white. For a couple of hours under the sunshine on the South Side of Chicago, we didn’t care about the color of each other’s skin. We simply watched some of the best baseball players this side of the Major League All-Star game. Maybe even better.”

“You say Ernie had charisma that you could feel from the stands?”

“Oh, yes. He not only charmed the fans with his sparkling eyes and his quick hands, he also captivated his teammates and the opposing players, too. I wouldn’t be surprised if his smile got the home-plate umpire to give him a break on the balls and strikes.”

Probably because I had watched too many scratchy, ancient newsreels and even more romantic comedies from the Golden Age, I envisioned Jack’s experience in sepia tones. Ernie and the other All-Stars were in fading black and white; had any color remained from that time, it would have looked like the worn-out leather of a disused baseball glove. I asked Jack if Ernie’s life would have been different if the Negro Leagues had remained independent and challenged Major League Baseball for fan interest. Could the Black ballplayers have done what Motown did for R&B? Own their sound? Play their own music? Keep their royalties?

Jack swatted away the idea. He told me that baseball was a business. Always had been. When the owners saw a way to make money off black hickory batters as well as blond maple ones, the days of the Negro Leagues were over. Reflecting back to the East-West Game, Jack cheered up. “Ernie was smooth in the field. Had amazing range and could go deep into the hole. But his unique talent was in his wrists. For such a small fellow, he sure could turn those powerful wrists on that ball. Didn’t matter whether it was a fastball, a curve, or a slider. All the same if the pitcher threw it high or low. Ernie could turn on the ball and give it a long ride. Really would have loved to see him showcase that talent at Wrigley. I could have exercised my lungs a few hundred more times: Back, back, back … Hey! Hey! Even that day at Comiskey, he put a smile on my face the way he jigged on the field. Oooh, boy! What a waste that he spent all those years rotting in prison.”

We both sat with that thought. I thought of my wife, the distance between us. Maybe Jack was thinking of his family or of all the ballgames he had covered.

Jack called for the check. Wanting to hold onto to him for a moment longer, I said, “Mr. Brickhouse, when you were my age, did you believe that the Negro Leagues stars could make it in the Major Leagues?”

“No, son. Not because they couldn’t play, but because I wasn’t sure they could deal with the ugly fans and some of the nastiness in the locker room.” He got up to leave, put on his gloves, and headed toward the door.

“Looks like they proved you wrong.”

Before leaving for the ballpark, Jack turned back from the exit. “Jackie and everybody that followed him sure proved me wrong. Wish Ernie could’ve played alongside them. Just can’t believe that that young fellow would’ve taken a life. On the day you find out what really happened to Declan Younger, I’m sure Ernie will consider himself the luckiest unlucky man on the face of the earth. Until then, I suggest you do more homework.”

I caught the reference to the famous quote from Lou Gehrig’s poignant farewell speech on July 4, 1939. I caught it as if it was a sharp line drive hit straight at me while I was playing third base anticipating a bunt. I had thought that the collegial announcer was going to shake my hand and wish me well. I imagined that he was going to be a wise old father figure who would guide me, his Brennan to my Cooper. But he was challenging me to be better than a Hollywood hero. “Thank you, Mr. Brickhouse,” I responded. “I promise you that I’ll find out by the Fourth of July.” I thought it would be romantic for Ernie to be fully free on the same day that Gehrig had made Yankee Stadium cry some five decades earlier.

Jack returned to the table where I was holding payment for the modest brunch. He took my twenty-dollar bill (with tip), slipped a crisp Benjamin on the table (grand slam of a tip!), held me by both of my shoulders. “C’mon, son. You know this is no academic exercise. We’re talking about two men’s lives: one dead and one living. You’re not going to get this done by the Fourth of July. You’re not going to get this done a couple of weeks later by the All-Star game either. Be realistic and keep plugging away at it. Maybe by the end of the season, you’ll have something. Like I said, I suggest you do some more research. Don’t call me again until you’ve done your homework. And when you do call, call me Jack. My father was Mr. Brickhouse.”

I took in the reproach. Stung like a schoolboy, I protested. “But I’ve got a plan. I’ve got a list of people involved with Declan Younger’s death. I’ll meet Ernie to work through what happened at the scene of the crime.”

Jack interrupted me. “Son, remember we don’t even know that there was a crime. Not too likely that you’ll get Ernie to talk. He’s pushed away his sad prison memories and now enjoys selling peanuts at Wrigley Field. Always has a big smile for the fans. A genuine smile that takes the rain out of a rainout.” He looked out a window, perhaps wondering if the weatherman’s forecast of a sunny day might be off, and maybe also reconsidering his assessment of Ernie’s congenial ballpark life. “But there’s another smile Ernie shows the world. This one’s a mask that hides a deep scar.”

Buy your copy of Double Play on the Red Line directly from Third World Press by clicking here.

My interview with the author is here.